Private Battles

Private Battles

About The Book

This book concerns the lives of four ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, and they are not famous people, and they are not professional writers. They write of their experiences in an honest, moving, humorous and brave way at a time when their lives and those of their friends were in danger, and they illuminate what it was like to live through the Second World War in a way that most books cannot – with immediacy and intimacy, and with great regard for commonplace detail. More than 60 years on, the reader stands in the diarists’ butcher’s queue, or sits by their side at work, and they whisper in our ear as if we had known them all our lives.

This book is also the last to be published in a trilogy but not the last in the sequence. The first of the three, Our Hidden Lives, concerns the three years of austerity following the war. The second, We Are At War, covers the start of the conflict until the middle of the Blitz in October 1940. Private Battles takes up the story from November 1940 to May 1945. Needless to say, this was not an entirely planned order of events.

A few years ago I was asked by my editor whether I thought there might be a book in the Mass Observation archives at the University of Sussex. I had only heard vaguely of Mass Observation. I knew it had been started in the late-1930s by three men – Tom Harrisson, Humphrey Jennings and Charles Madge – who were interested in what ordinary people thought about their lives and the world around them. They began by observing them close at hand in their factories and pubs, and they asked them to write about certain issues – their political views, the prospect of war, how they spent their Saturdays. When war looked inevitable, the Mass Observers were also asked to keep personal journals about their daily activities and send them to an office in London each month. Several hundred people of all ages and backgrounds wrote from all over Britain, and they wondered what possible purpose their daily rituals and regular engagements would serve.

Initially, their opinions were used to gauge morale; the government ministers took a keen interest in Mass Observation, for they recognised it as a true and spontaneous expression of the mood of the country. Subsequently, historians have consulted the diaries for all manner of reasons, the task made easier when the material was deposited by Tom Harrisson at the University of Sussex in the late 1960s.

When I first encountered the diaries, I was struck by their great richness and variety, and by the daunting amount of pages to examine. Some correspondents had sent only the most perfunctory accounts (‘woke up … went to work … came home’), but some wrote several pages a day about every aspect of their lives, devoting many hours each week to write up notes they had often taken surreptitiously. I was surprised that more historians had not utilised the diaries in a comprehensive way, using larger, more revealing passages rather than little snippets. I decided to try to tell the story of the war and its aftermath in two ways: in the usual chronological format dominated by the big turning points, and also in a manner that juxtaposed several lives to provide a level of personal detail not generally considered relevant (but in truth highly instructive).

I began with the post-war period, partly because there were fewer diarists to read and select from, and partly because it was a period that had been relatively under-examined. The result was Our Hidden Lives, an account from VE Day to the birth of the NHS as witnessed by five writers. The book struck a chord, sold well, and was made into a BBC film. I loved working on it, and was keen to edit some more. The immediate thought was to resume the stories of the diarists for another few years, but their output dwindled and became less involving. So I looked at the diaries that had been written during the war, initially fearful that they wouldn’t yield enough fresh material to stand up well against the many other war books published every month.

But I was wrong. The diarists’ lives were unique, and We Are At War revealed fascinating and unanticipated insights. This third book completes the story. There are only four writers this time, for the period covered is longer, but I hope their observations are no less engaging and rewarding.

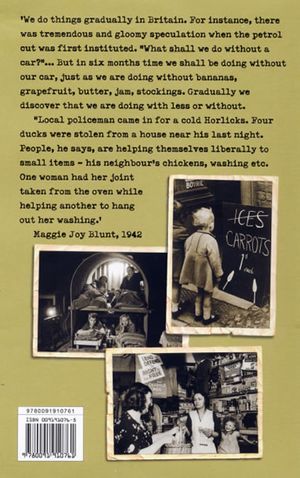

The grand theme is a simple one: just getting through it all. An early title for this book was Keeping It Together, a phrase the diarists would never have used but would easily have understood. How to get enough nutrition. How to pay the fines imposed for not blacking out at night. How to feel that you were doing something valuable for your country. How to criticise the government and those in authority without appearing unpatriotic, ungrateful or Communist. How to scheme, particularly where food was concerned. How to plan for a post-war world, as hard sometimes as that was to envisage. How to avoid being ill all the time (poor nutrition again, working longer days, standing around for hours in food and transport queues). And then there was the question of how not to be killed.

Taken as a whole, two other patterns emerge, both forcible rejoinders to the notion that we were all pulling together during these years. The diarists writing here – by no means a representative sample of the country’s mood, but nonetheless a valuable snapshot of it – describe a wartime Britain we may be a little unfamiliar with. Displays of genuine camaraderie and the Blitz/Dunkirk spirit of legend are matched by acts of selfishness and expressions of spite. Usually these are the result of the daily grind: beating someone else to the rationed fruit or shoes, feeling resentful about the lack of support when fire-watching. But there is a deeper malaise too, a belief that the war is not being prosecuted well and that those in power do not understand the prolonged suffering of the less privileged. Churchill is by turns revered, mocked and scolded, his ministers treated with equal parts respect and disdain.

Two of the diarists may be familiar. Maggie Joy Blunt, who has appeared in both previous volumes, is a frustrated freelance writer in her early 30s, living in Burnham Beeches near Slough. She begins work as a publicity and marketing officer for an alloys firm involved in aircraft manufacture, but her heart is elsewhere: with her many friends in London, with her male friend S fighting in Europe, with her literature and love of politics, with her cats. She does not contribute as frequently as the other diarists, but she writes with heartfelt passion and a memorably lyrical turn of phrase.

Readers of We Are At War will remember Pam Ashford, the secretary at a coal shipping firm in Glasgow. She is 38 when we meet her again, still living with her mother and in daily pursuit of both office gossip and affordable food. She changes jobs twice in the course of these diaries, and we follow her emotional turmoil as she leaves and meets new colleagues. She brings a fascinating insight to the American presence in Glasgow, and she in enthralled and horrified by their modern manners and morals.

And then there are two new writers, both men. Edward Stebbing is a soldier in his early twenties. He was born in Essex, and enjoyed a conventional grammar school and Church of England upbringing. His experiences as a private in Aldershot, London, Yorkshire and Scotland he finds disorientating, but he reports faithfully the views of his fellow recruits. He is delighted to be discharged in 1941: ‘My service in the Army has seemed to me a sheer waste of time. Now, paradoxically, I am going to see what the war is like.’ He finds a job at a hospital in Hertfordshire and writes with great frankness of his thoughts and those of his workmates and landlady as the war progresses; as he concludes, ‘what is difficult for historians to convey … is that such a multitude of different events [are] happening simultaneously’.

The fourth diarist is Larry du Parc, a 37-year-old research chemist in Hertfordshire, a husband and father, a keeper of hens and keen Quaker, a determined individualist. In the days before iPods and mobile phones, people practise their recorders on the train home. Well, not everyone; but Larry du Parc does, and he does other unorthodox things too. He shuts his son Laurie in the greenhouse to calm him down, and he reports on the amount of blood spilled at a children’s birthday party. Because of the secrecies of war we never really discover quite what it is that Mr du Parc does at work, although we do know it is part of the effort to defeat the Nazis, and we also know that many of his efforts do not go as planned.

As ever, the glory is in the minutiae. We learn about the exact nature of a shop window’s contents and the meals they inspire; we read the precise words spoken in favour and disgruntlement at a particular turning in a far-flung battle. We envisage a scene of such vividness at a job interview or gathering of friends that we have no trouble rooting for the participants. There is no hindsight in these diaries, no ability for the writers to edit with the benefits of retrospect and a more refined judgment. Our four writers express not only fortitude but also courage that their words would not be misused. Their agreement with the founders of Mass Observation and its trustees specified that their work would be used as they saw fit and fair, and their identity would be protected. As with the first two books, this arrangement has been upheld (with the exception of Edward Stebbing, who previously published his wartime entries through a local press; his son kindly agreed that his real name could be used again here). All the other names, places and events are unchanged, although the total length of the diaries has been greatly reduced. Unedited, the full text would run to about 800,000 words, or more than four times the present length. No words have been added, although very occasionally the sequence of a particular entry has been rearranged to improve clarity. There are several gaps in the writers’ journals, caused by illness, time spent revising for exams, pressures of work. Sometimes, I think, entries have just got lost in the post or were mislaid in the years before Tom Harrison transferred them from London to Sussex.

But much of an important and engrossing nature survives, and this is what may be learnt from this volume alone: why there was an increased demand for pianos; how best to feed canaries at a time of seed shortage; what happened when you agreed to ‘See the Lovely Lovelies’; how unpopular was Neville Chamberlain even as he fell ill; how Sugarettes proved a poor substitute for real sugar; what happened when official summertime lasted until November; how not to secure an additional personal supply of eggs; and how much Iceland craved British cosmetics and underwear.

We may also read how successful was Woolworth’s restaurant, and the fact that the cooking was done by electricity; precisely why the Italians had given up fish and chips; how difficult it was to buy a comb; how many days it usually took for the government to admit that German claims about damage inflicted on the Allies was in fact true; how wartime wedding cakes were really a sham and excessive marzipan was illegal; how best to pilfer goods from wooden crates at the docks; how the latest offerings of ‘fish flesh’ were probably whale; and how one diarist was personally affected by a particularly gory event at Gracie Fields’ house.

And then we may discover just why ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ became the American national anthem; how small boys were employed in the war against VD; how Sir William Beveridge was considered conceited and his Report mistrusted; how there was strong belief that Germans should face post-war firing squads and not trials; how short films about welding and forgings proved to be both rewarding and popular; how tomatoes can have therapeutic uses in the treatment of anxiety; and how the ending of the conflict was expected almost a year before it came.

As one protagonist may have put it, this is not the whole story, it is not even half the story, but it is perhaps one of the best ways of telling a part of the story. Everyone has their own individual experiences of the war, but human hopes, anxieties, and pleasures don’t vary that much from person to person, and don’t change very much over time. If you lived through it, you will recognise these emotions. And if you were too young, these diarists have done all they can to tell you what it was really like.

Extract from Private Battles Chapter 1

THURSDAY, 31 OCTOBER 1940

Maggie Joy Blunt

Metal factory worker living in Burnham Beeches, near Slough, age 31

The winter is here. It seems to have come so quickly. Yesterday I found the dahlia leaves blackened by frost and I lifted and stored the tubers and cut the remaining flowers. They are in a vase now in front of me: their delicately crinkled petals spread in perfect circles of pale colour. I didn’t realise dahlias were so lovely. What shall I be doing and feeling, and what shall I have done and felt, by the time those tubers bloom again …

SATURDAY, 2 NOVEMBER

Ernest van Someren

Research chemist in Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, age 37

Jean R. came to see us. We sat and talked most of the afternoon and evening, largely about incidents in London. She has just moved from an old house very near a railway to a steel and concrete block of flats. She told us about a woman having a bath in Kentish Town whose house was damaged by a very close hit, so that her bath slid down into the street without spilling the water or hurting her in any way. It was dark too.

MONDAY, 4 NOVEMBER

Pam Ashford

Secretary in coal shipping firm, Glasgow, age 38

At 2.45am the alert woke me up, but I went to sleep again, and did not hear the all clear; this is said to have gone at 3.50. I have been surprised by the changed attitude so many people are showing – they stayed in bed. Familiarity must be one factor, and I should think the cold nights another.

My friend Miss Whittan was ’phoning London friends this morning and they reported that last night – the first for 56 nights without an alert – was so quiet as to be ‘eerie’. There they were in their shelters expecting something to happen and nothing did. The ears get used to the noise and then quiet keeps one awake.

Miss McKirdy has heard of a house that was bombed in London, and immediately the salvagers began to go all over the debris looking for a pair of pink corsets. The owner had £2000 sewn in and had not happened to be wearing the garment at the time the bomb fell.

Ernest van Someren

Up early for Jean to get a coach back to work. A good post, letters from my brother and bro-in-law in RAF and a note from my mother with some ham from my sister in USA. Tony, my brother, has been moved from Scotland to Lancashire to a RAF training camp where he is allowed to do some consultant work as a psychiatrist, which he had hoped to do.

During the day a parcel arrived from Tessa with assorted sweets and two pairs of nylon stockings. After we had sampled the sweets we found a letter saying that they were for Esmee and her two boys. We sent on the rest of the sweets the next day.

In the evening wrote diary and letters. It was fairly noisy.

Maggie Joy Blunt

Heart of my heart! It seems six or seven bombs have just fallen outside my back door. I heard a plane and then zzzoom! zzzoom! zzzoom! – one after the other. I felt the ground shaking and dived for the table. We have had bombs at H Corner which destroyed two council houses and the landmine in the Beeches but nothing as near as this. What damage now is done? I heard the soldiers stationed in the woods shouting ‘Lights! These people aren’t blacked out at all!’ But it’s not easy to keep a slither of light from showing now and then. The times I have pulled and tacked and padded my black-out.

The silence now … and the darkness! Outside never was such a dark night and that one plane swooping from the clouds, dropping its bombs without warning … I have heard no siren … In this quiet, withdrawn spot it is the unexpectedness of such an event that is so terrifying. I would rather be in a town and hear the barrage guns.

Read the full extract .pdf format (114k)