All the Knowledge in the World

All the Knowledge in the World

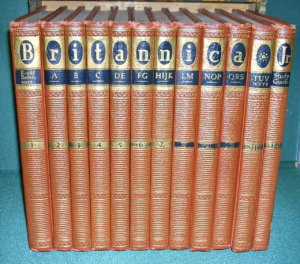

From the Introduction: On Friday, 4 June 2021, I made peterhodgson1959 an offer for his encyclopaedias. He was selling what he described on eBay as ‘Encyclopedia britannica pre-assembly suppliment set 4th, 5th & 6th editions’. Seven tall volumes, condition ‘acceptable’. They dated from 1815 to 1824, with articles on acoustics, aeronautics and Spain. I was intrigued by the prospect of a twenty-nine-page entry on Chivalry, and frightened by the forty-page treatise on Equations. I hoped to learn what 1819 knew about Egypt, and what 1824 understood about James Watt. peterhodgson1959 had set the opening bid at £44, which I liked for its randomness. I offered him £50 to end the auction a few days early and was delighted when he agreed. Peter told me he had owned the books for about twelve years. ‘For some reason ’he had decided to obtain a set of each of Britannica’s fifteen monumental editions spanning 1768–2010, several hundreds of volumes and hundreds of millions of words. But now he was downsizing his home, and evaluating his reasoning, and things had to go. My seven supplementary volumes arrived via UPS four days later. ‘Acceptable ’may have been better described as ‘flaky ’or even ‘deplorable’, because they were foxed, water-stained, falling apart and they smelt of armpit, but they were still wholly legible and fascinating, and more than acceptable to me. They were additionally acceptable because all but one of the opening pages carried the elegant signature of P.M. Roget. Peter Mark Roget, a well-regarded physician and active Fellow of the Royal Society, had not only found time between teaching and surgery to purchase the greatest encyclopaedia of his age, but also, in his late thirties, to contribute regular articles. At the front of Volume 1 he had written a list of his entries: Ant, Apiary, Bee, Cranioscopy, Deaf & Dumb, Kaleidoscope and Physiology.

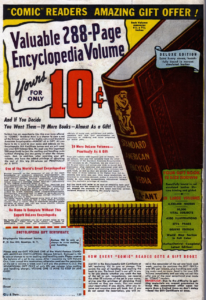

And of course he had found time for something else, for while he was writing his Britannica entries he was also writing/ composing/compiling/producing/penning his Thesaurus. I was enchanted by the conflation of these two great reference works, both of which I’d consulted all my life. A week later I went on eBay again. I was becoming hooked on old knowledge – and how cheap it was. A seller called 2011123okay from Haywards Heath was willing to part with a complete nineteen-volume Children’s Britannica from 1993 for 99p. Davidf7327 from Buckfastleigh was selling a twenty-six- volume 1968 Britannica (with yearbook and atlas) for £1. And cosmicmanallan from the Rhymney Valley offered a twenty- four-volume set of the fourteenth edition, condition good, for £3. There was a lot of talk in the papers at the time of how we were all searching for certainty in our lives: amid Covid-19 and disruptive social change, we yearned for an element of stability and control – something trustworthy and authentic, the reliable pre-pandemic world in reliable physical form. Not the case with encyclopaedias, it seemed; not if the items on eBay were anything to go by. Someone calling themselves thelittleradish was selling the complete fifteenth edition, the last in the line, originally published in 1974, thirty-four volumes including yearbooks. This particular set was last updated in 1988, and they were in near-perfect condition. The starting price of the auction was £15. I thought they might reach £30 or £40. But no one else wanted them, so the set was mine for £15, which was obviously incredible considering that it contained the work of around 4000 authors from more than 100 countries. And these authors weren’t just random people. They were experts, PhD people, men and women who had not only attained excellence in their specialisms, but were able to share their knowledge with others, with me. According to Britannica’s own account, the editorial creation of this work cost $32 million, exclusive of printing costs, which made it the largest single private investment in publishing history. And the price now – 44p a volume, less than the cost of a Mars bar – made it the best value education one could possibly buy, and the fastest depreciating assemblage of information ever known. If the market assigned true worth, then the stock in encyclopaedias had tumbled into the basement, if not back into the soil. Of course, I had to add petrol to that. I drove down to Cambridge – Cambridge! – to collect the set in my seething Toyota (Cambridge University Press had published Britannica in its heyday at the beginning of the twentieth century). thelittleradish turned out to be a thirty-two-year-old named Emily, who was not particularly little and lived in Sawston, about seven miles from the city centre, and she joked that the extra weight I was about to load into my car was nothing, for she’d just had to carry all the books down the stairs. They were waiting for me in the front room, six piles spread across one wall, and as I shifted four books at a time into my boot, and then my back seats, and then my front seat, Emily apologised for the possible scatter of cat hair. Emily told me she had never actually consulted any of the volumes herself. During my drive to her home I assumed she’d inherited the set from a recently departed parent or grandparent, and their value to her wasn’t justifying the space they were taking up, and her loss would be my gain. But no: she had a side hustle buying and selling on eBay, usually selling for more than she bought. Not this time. She had bought the set three months ago from someone who said his children had used them all through school, and now that they were young adults he had no use for them any more. She didn’t want me to reveal how much she’d paid for them, but it’s safe to say she wouldn’t be buying any more sets for profit. As we’d both just experienced, an old encyclopaedia was about as popular as a burst balloon. Emily’s young daughter toddled through from the kitchen. ‘You don’t want to keep these for her? ’I asked her mother, but I had already guessed her reply.

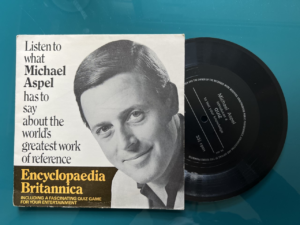

And these authors weren’t just random people. They were experts, PhD people, men and women who had not only attained excellence in their specialisms, but were able to share their knowledge with others, with me. According to Britannica’s own account, the editorial creation of this work cost $32 million, exclusive of printing costs, which made it the largest single private investment in publishing history. And the price now – 44p a volume, less than the cost of a Mars bar – made it the best value education one could possibly buy, and the fastest depreciating assemblage of information ever known. If the market assigned true worth, then the stock in encyclopaedias had tumbled into the basement, if not back into the soil. Of course, I had to add petrol to that. I drove down to Cambridge – Cambridge! – to collect the set in my seething Toyota (Cambridge University Press had published Britannica in its heyday at the beginning of the twentieth century). thelittleradish turned out to be a thirty-two-year-old named Emily, who was not particularly little and lived in Sawston, about seven miles from the city centre, and she joked that the extra weight I was about to load into my car was nothing, for she’d just had to carry all the books down the stairs. They were waiting for me in the front room, six piles spread across one wall, and as I shifted four books at a time into my boot, and then my back seats, and then my front seat, Emily apologised for the possible scatter of cat hair. Emily told me she had never actually consulted any of the volumes herself. During my drive to her home I assumed she’d inherited the set from a recently departed parent or grandparent, and their value to her wasn’t justifying the space they were taking up, and her loss would be my gain. But no: she had a side hustle buying and selling on eBay, usually selling for more than she bought. Not this time. She had bought the set three months ago from someone who said his children had used them all through school, and now that they were young adults he had no use for them any more. She didn’t want me to reveal how much she’d paid for them, but it’s safe to say she wouldn’t be buying any more sets for profit. As we’d both just experienced, an old encyclopaedia was about as popular as a burst balloon. Emily’s young daughter toddled through from the kitchen. ‘You don’t want to keep these for her? ’I asked her mother, but I had already guessed her reply. The printed Britannica is printed no more, but it exists as myth, as plagiarised schoolboy homework, as parental guilt-ridden purchase, as a salesman’s silver-tongued wile, as evidence of a ridiculously bold publishing endeavour, and as a mirror to the extraordinary growth of cultured civilisations. My book is not an encyclopaedia of encyclopaedias; it is not a catalogue or analysis of every set in the world, just those I judge the most significant or interesting, or indicative of a turning point in how we view the world. The only mention of the American Educator Encyclopaedia and Dunlop’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Facts, for example, has just occurred. If your favourite is Johann Heinrich Alsted’s Encyclopaedia Septem Tomis Distincta of 1630, I can only apologise for its absence. Specialist guides are also missing – the Encyclopaedia of Adoption, say, and the Christopher Columbus Encyclopaedia, brilliant as they both might be. No room either for the Encyclopaedia of World Crime (six volumes, Marshall Cavendish, 1990), or even the Concise Encyclopaedia of Traffic and Transport Systems (Pergamon Press, 1991, $410). If you live in the Netherlands, I hope you already know all about the Grote Winkler Prins Encyclopedie (twenty-six volumes, Elsevier 1985–93). Almanacs and catalogues of miscellany – astrological charts, lists of capital cities, seasonal gardening tips – are also excluded. My history focuses on the West, on the great European and American tradition. Chinese and South American volumes get a look-in along the way, but they are exceptions in my attempt to record not just the monumental achievements of encyclopaedias as objects, and the admirable if sometimes maniacal ambitions of their compilers, but to set these objects within the framework of Western knowledge-building. They were as much a part of the Enlightenment as they were the Digital Revolution. So what had happened to this brilliant world? How had something so rich in content and inestimable in value become so redundant? Why were so many people giving these wonderful things away for almost nothing? I knew the answers, of course: digitisation, the search engine, social media, Wikipedia. The world was moving on, and access to knowledge was becoming faster and cheaper. But I also knew that information was not the same as wisdom, any more than the semiconductor was the same as the turbine. I was fairly certain that relinquishing so much accumulated knowledge so dismissively was unlikely to signal good things. At a time when researchers at MIT had found that fake news spread six times faster on social media than factual news (whatever that is), and when false information made tech companies much more money than the truth (whatever that is), we should necessarily ask whom we can trust. Despite its numerous and inevitable errors, I have always trusted the intentions of the printed encyclopaedia and its editors. That we don’t have the space in our homes (and increasingly our libraries) for a big set of books suggests a new set of priorities; depth yielding to the shallows. The process of making an encyclopaedia informs the worth we place on its contents, and to neglect this worth is to welcome a form of cultural amnesia. This book is as much about the value of considered learning as it is about encyclopaedias themselves. It is about the vast commitment required to make those volumes – an astonishing energy force – and the belief that such a thing will be worthwhile. Those who bought them did so in the hope of purchasing perennial value. An encyclopaedia is a publishing achievement like no other, and something worth celebrating in almost every manifestation.

The printed Britannica is printed no more, but it exists as myth, as plagiarised schoolboy homework, as parental guilt-ridden purchase, as a salesman’s silver-tongued wile, as evidence of a ridiculously bold publishing endeavour, and as a mirror to the extraordinary growth of cultured civilisations. My book is not an encyclopaedia of encyclopaedias; it is not a catalogue or analysis of every set in the world, just those I judge the most significant or interesting, or indicative of a turning point in how we view the world. The only mention of the American Educator Encyclopaedia and Dunlop’s Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Facts, for example, has just occurred. If your favourite is Johann Heinrich Alsted’s Encyclopaedia Septem Tomis Distincta of 1630, I can only apologise for its absence. Specialist guides are also missing – the Encyclopaedia of Adoption, say, and the Christopher Columbus Encyclopaedia, brilliant as they both might be. No room either for the Encyclopaedia of World Crime (six volumes, Marshall Cavendish, 1990), or even the Concise Encyclopaedia of Traffic and Transport Systems (Pergamon Press, 1991, $410). If you live in the Netherlands, I hope you already know all about the Grote Winkler Prins Encyclopedie (twenty-six volumes, Elsevier 1985–93). Almanacs and catalogues of miscellany – astrological charts, lists of capital cities, seasonal gardening tips – are also excluded. My history focuses on the West, on the great European and American tradition. Chinese and South American volumes get a look-in along the way, but they are exceptions in my attempt to record not just the monumental achievements of encyclopaedias as objects, and the admirable if sometimes maniacal ambitions of their compilers, but to set these objects within the framework of Western knowledge-building. They were as much a part of the Enlightenment as they were the Digital Revolution. So what had happened to this brilliant world? How had something so rich in content and inestimable in value become so redundant? Why were so many people giving these wonderful things away for almost nothing? I knew the answers, of course: digitisation, the search engine, social media, Wikipedia. The world was moving on, and access to knowledge was becoming faster and cheaper. But I also knew that information was not the same as wisdom, any more than the semiconductor was the same as the turbine. I was fairly certain that relinquishing so much accumulated knowledge so dismissively was unlikely to signal good things. At a time when researchers at MIT had found that fake news spread six times faster on social media than factual news (whatever that is), and when false information made tech companies much more money than the truth (whatever that is), we should necessarily ask whom we can trust. Despite its numerous and inevitable errors, I have always trusted the intentions of the printed encyclopaedia and its editors. That we don’t have the space in our homes (and increasingly our libraries) for a big set of books suggests a new set of priorities; depth yielding to the shallows. The process of making an encyclopaedia informs the worth we place on its contents, and to neglect this worth is to welcome a form of cultural amnesia. This book is as much about the value of considered learning as it is about encyclopaedias themselves. It is about the vast commitment required to make those volumes – an astonishing energy force – and the belief that such a thing will be worthwhile. Those who bought them did so in the hope of purchasing perennial value. An encyclopaedia is a publishing achievement like no other, and something worth celebrating in almost every manifestation.

Like an old atlas, old encyclopaedias tell us what we knew then. Not so long ago – just before we all got computers in fact – they did more than any other single thing to shape our understanding of the world. It is no surprise that many of the greatest minds contributed to their success, from Newton and Babbage to Swinburne and Shaw, from Alexander Fleming and Ernest Rutherford to Niels Bohr and Marie Curie. Leon Trotsky wrote about Lenin. Lillian Gish considered motion pictures. Nancy Mitford courted Madame de Pompadour. W.E.B. Du Bois summarised ‘Negro Literature’. Tenzing Norgay tackled Mount Everest.

Like an old atlas, old encyclopaedias tell us what we knew then. Not so long ago – just before we all got computers in fact – they did more than any other single thing to shape our understanding of the world. It is no surprise that many of the greatest minds contributed to their success, from Newton and Babbage to Swinburne and Shaw, from Alexander Fleming and Ernest Rutherford to Niels Bohr and Marie Curie. Leon Trotsky wrote about Lenin. Lillian Gish considered motion pictures. Nancy Mitford courted Madame de Pompadour. W.E.B. Du Bois summarised ‘Negro Literature’. Tenzing Norgay tackled Mount Everest.

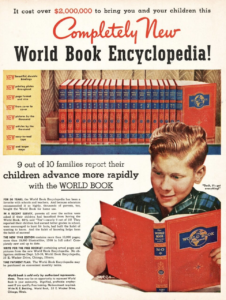

Encyclopaedias were once as common as cars. Attracting both esteem and derision, they occupied the literature because they occupied the life – the weighty backdrop to an intelligent discourse, the stern status symbol on the shelf, a reliable target of satire. I’ve come to rob your house, a man tells a woman on her doorstep in the first series of Monty Python. Well OK, she replies, just as long as you’re not selling encyclopaedias. When I returned to eBay I found a complete set of Britannica from 1997 selling for 1 pence. I looked at my screen again: it really was £0.01. The seller described the books as ‘pristine’. There was even a bonus book, Science and the Future, predicting everything but the demise of the encyclopaedia. I began to wonder what a set of unwanted encyclopaedias cheaper than firewood said about the value we place on information and its history, particularly at a time increasingly decried as rootless and unstable. Perhaps this story will help us understand ourselves a little better, not least our estimation of what’s worth knowing in our lives, and what’s worth keeping.

All the Knowledge in the World Extract

WIKIMANIA

Each summer, the staff of Wikipedia get together with their most fanatical contributors for a five-day conference called Wikimania, a sort of WrestleMania for the brainy and pedantic. There is soul searching, navel gazing, pulse taking and crystal balling, not forgetting punch pulling and verbal flame throwing. Popular issues for discussion include inclusion, deletion, citation, representation, notability, harassment of editors, empowerment of users, and the open-source software operating system called Ubuntu. Astonishingly, perhaps, the event sells out fast. In 2014 the venue was London, in 2018 Cape Town, in 2019 Stockholm.

Like the textual behemoth that inspired it, Wikimania goes high and low. You turn up from all corners of the globe, get the bright yellow T-shirt, and within minutes you’re embedded in a break-out group called ‘Wiki Loves Butterfly’, or ‘Serbia Loves Wikipedians in Residence’, or ‘Let’s Completely Change How Templates Work!’. The conference also holds board meetings, and pledges to do better next year on issues of gender and racial diversity. It even announces its Wikimedian of the Year, a title awarded in 2020 to Emna Mizouni, a Tunisian human rights activist praised for organising the conference WikiArabia and contributing to the photographic project Wiki Loves Monuments.

And then, as the sky darkens, and should you have the stomach for such things, you may join the gatekeepers of the world’s knowledge as they knock back tequila-based wikishots and indulge in their ‘passion projects’. You would be surprised if these didn’t include making snow globes, real-life Quidditch, ‘being awesome ’and jail-friendly power yoga, at the very least.

Wikipedia is a universe unto itself, its ambition unequalled and its scale unprecedented. Its staff are fond of a single phrase: ‘Thank God our enterprise works in practice, because it could never work in theory. ’In theory, Wikipedia should be a disaster. The work of world experts and world amateurs, creators and vandals, anarchists and trainspotters, super-grammarians and super-creeps, many hundreds of thousands of each from all the world’s nations, every one vaguely suspicious of everyone else, some using Google Translate in hilarious ways, all battling for some sort of supremacy in a multiverse of ultimate truth – that doesn’t bode well. And yet that’s what Wikipedia is – an errant community of career-long academics and lone-wolf information crackpots that continues to create something of brilliance with almost every keystroke.

Read the full extract.pdf format (95kb)