A Notable Woman

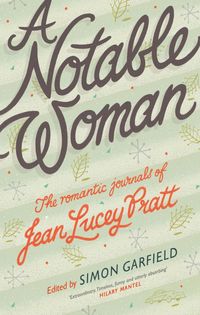

A Notable Woman: The Romantic Journals of Jean Lucey Pratt

This is a book – a long book, a unique book – about a woman named Jean Lucey Pratt. She wasn’t famous, and she wasn’t particularly remarkable, but she did one remarkable thing: in April 1925, at the age of 15, she began writing a journal, and she didn’t put down her pen for sixty years. She produced well over a million words, and no one in her family or large circle of friends had an inkling until the end.

She wrote – legibly, in fountain pen, usually in Woolworth’s exercise books – about anything that amused, inspired or troubled her, and the journal became her only lasting companion. She wrote with aching honesty, laying bare a single woman’s strident life as she battled with men, work and self-doubt. She increasingly hoped for posthumous publication, and her wish is hereby granted; the pleasure, inevitably, is all ours.

I first fell under Jean Pratt’s spell in the autumn of 2002, but she had another name then. I was visiting the University of Sussex, immersed in Mass Observation, the organisation founded in London in the late 1930s to gain a deeper understanding of the thoughts and daily activities of ‘ordinary people’. As the project evolved and the war began, hundreds of people agreed to submit their personal diaries, and Jean Pratt was among them. Most of the diaries (and diarists) were, of course, anything but ordinary: they were diverse, proud, intriguing, trivial, insightful, objectionable, and candid. I was at the university to compile a book of this extraordinary material.

Over the next few visits I selected five writers who were different from each other in age, geographical location, employment and temperament. The result was the book Our Hidden Lives, which then led to two other Mass Observation compilations, We Are At War and Private Battles (you’ll find details of them all on this site).

The only diarist to feature in all of them was Jean Lucey Pratt, whom I renamed Maggie Joy Blunt. (I changed all the names: this was in keeping with the broad understanding of Mass Observation’s founders and contributors – their words would be used as MO saw fit, but their identities would be protected, a liberating agreement, enabling frank contributions and freedom from prying eyes.)

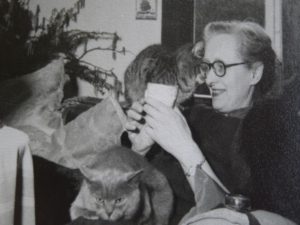

Jean lived in a small cottage in the middle of Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire. During the war she had taken a job in the publicity department of a metals company, where the tedium almost swallowed her. She had been a trainee architect, but what she really wanted to do was write and garden and care for her cats. She took in lodgers; she read copiously; she hunted down food and cigarettes. She researched a biography of an obscure Irish actress at the British Museum. And she kept track of her life in the most lyrical of ways.

Many readers claimed her as their favourite, and wrote asking whether there was any more. Fortunately there was more. Although Jean Pratt had died in 1986, she had a niece who was still alive. And the niece had treasures in the attic.

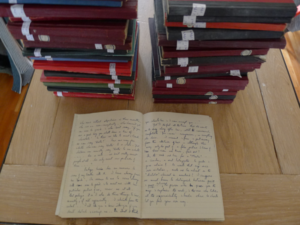

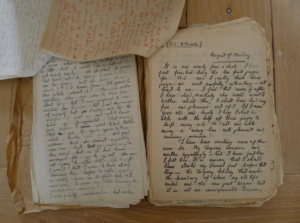

There were several boxes’ worth; Jean had kept diaries not just for Mass Observation, but for her entire life. Two fat folders contained about 400 loose pages, and then there were the exercise books, 45 in all.

There was also a brief biographical sketch, typed in April 1946, when Jean was 36. ‘I was born on Oct. 18th 1909 in the parish of Wembley, Middx. My father was an architect, living with wife and son of 9 years at that time, in a comfortable, detached, 4-bedroomed house which he had designed. An acre or so of garden surrounded the house…My mother was an accomplished pianist before she married, and had intended for herself a musical career. Her youngest brother…went into the tobacco business against his father’s wishes. The business prospered, opened a retail shop in BondStreet and a branch in New York. It was known as Philip Morris Ltd…and it was due to my uncle’s enterprise that I possessed the means for the education I received and all my subsequent economic independence.’

In 2004 I sat with the journals at her niece’s house for a few hours, and made notes. The sentences I recorded included this terse summation of Jean’s life to date, composed in 1926 when she was almost 16: ‘Bare legs and the wonderful silver fountain of the hose. Daddy in a white sweater. School. Very small, very shy. The afternoon in May – taken by mother to Penrhyn. Learning how to write the letters of the alphabet. A beautiful clean exercise book and a new pencil. Miss Wade at the head of the dining room table and me at her right. Choking tears because of youth’s cruelty…’

Very small, very shy. I thought the journals were wonderful – not only their contents, but their physicality; not only the observations but the persistence. I was persistent too: it wasn’t until December 2013 that I was able to begin work editing Jean’s writing, a project that took three times longer than expected but didn’t feel like a chore for a minute. The journals and other papers arrived in three large boxes at my home in London. They smelled faintly of tobacco; they were redolent of pressed flowers and meat paste. I felt privileged, daunted, and responsible. Most of the journals had remained unopened and unread since the day their writer had laid them aside.

Jean’s diaries are rambling, anti-climactic, inconsistent, repetitive and opaque, but for the most part they are a revelation and a joy. Not only fascinating to read and startling in their candor, but also funny, unpredictable and so engagingly and gracefully written that I couldn’t wait to turn the next page for further adventures. The questing displays of loving and longing (for romance, for life’s meaning) are brave and meltingly disarming; her devotion to her cats is heartbreaking; her comic timing owes something to the music hall. At times I felt like an intruder; at others a confidant; I wanted both to shake her and hug her. I found myself rooting for her on every page, willing her to win that tennis game or persuade a man to stay. The life that I had first encountered in her wartime Mass Observation entries now stretched back to her childhood and forward to her old age, a snapshot transformed by a greater depth of field. I knew of no other account that so effectively captured a single woman’s journey through two-thirds of the 20th century, nor one written with such self-effacing toughness.

For the modern reader the journals provide many satisfactions. The writer’s emotions are universal and enduring: we empathise with her ambitions, disappointments and yearnings. Cumulatively, the journals envelope like a novel: the more one reads, the more one cares what happens next. I frequently thought of Jean’s latest challenge or calamity upon waking, and stayed up late to read the latest installment.

How to sum up a life’s work? Certainly we may regard it as forward-thinking. She was clearly not the first woman to engage with the apparently mutually exclusive possibilities of spousal duty and career, but her modernity singled her out from her parents and the herd. Most of all I admired her candidacy, the raising of her hand. This is an exposing memoir, an open-heart operation. One reads it, I think, with a deep appreciation of her belief in us.

The dual responsibility (to Jean and her new readers) to deliver a volume that was both manageable in length and true to her daily experience – that is, something both piecemeal and cohesive – has resulted in a book incorporating only about one-sixth of her written material. I do hope she’ll be happy with the result. Looking for love all her life (from friends, from men, from pets, from teachers, from customers), Jean Pratt may have found her fondest devotees only now, among us, her fortunate readers.

A Notable Woman

Frontispiece

This document is strictly private. All that is written herein being the exact thoughts, feelings, deeds and words of Miss JL Pratt and not to be read thereby by anyone whatsoever until after the said Miss JLP’s death, be she married or single at the date of that event. Miss Pratt will, if she be in good state of mind and body, doubtless leave instructions as to the disposal of this document after her decease. Should any unforeseen accident occur before she is thus able to leave instructions, it is her earnest desire that these pages should be first perused by the member of her family whom she holds most dear that will still be living and to whom the pages may be of interest.

Signed: JL Pratt 1926 [Added to beginning of diaries some months after commencement.]

Chapter 1. Into a Cow

Saturday, 18 April 1925 (aged 15)

I have decided to write a journal. I mean to go on writing this for years and years, and it’ll be awfully amusing to read over later. We’re going to Torquay next week. I feel so thrilled! We start on Tuesday and drive all the way down in our own car. We only got it at Xmas, and Daddy has only just learnt to drive. It’ll be rather fun I think. It’s a Fiat by make. I’ve always longed for a car. I’m going to learn to drive it when I’m 16.

Do you remember Arthur Ainsworth, Jean? Funny bloke – he used to be in the Church Lads Brigade when Leslie was Lieutenant. He used to be my ‘beau’ then. He used to come and have morse lessons with Leslie. He used to put his arm round me when he was learning – I could only have been 8 then! And we used to play grandmother’s footsteps in the garden and he tried to kiss me – he did kiss my hair. I was quite thrilled – but not overmuch. He used to be sort of Churchwarden at the Children’s Service on Sunday afternoon and I used to giggle all the time – even though Mummy was there. I think she knew! She didn’t say anything though, the darling – oh how I miss her. I wish she were here now. I’d have been all I could to her.

Anyway, who was my next beau? I can’t remember. I think it was Gilbert Dodds. I’ve got them all down in secret code in my last year’s diary. Let’s go and fetch it.

Yes, here it is – I’ve got it down like this: PR (past romances)

1. AA

6. R

Gilbert Dodds was the 2nd. He was awfully good looking. He lived at Ealing. The 3rd was Tony Morgan. I hated him, but in my extreme youth I used to go to school with him and I used to go to tea etc. Daddy once suggested he should be my dance partner – was furiously flattered in a way – but I always blushed when he was mentioned. I have an awful habit of blushing, it’s most annoying. They’ve left Wembley now thank goodness. Mr Morgan ran away or something. I couldn’t bear Mr Morgan either. He sniffed and always insisted on kissing me. He had a toothbrush moustache and it tickled and oh I hated it. I hid behind the dining room door once till he’d gone.

The next one was a waiter. It was at the Burlington at Worthing and he used to gaze at me so sentimentally. He used to get so nervous when he waited at our table. I never spoke to him – it’s much nicer not to speak. The next one was a choir boy at St Peter’s. I used to make eyes at him each Sunday and we used to giggle like mad. He was quite good looking with fair hair and pale, rather deceitful blue eyes. At the beginning of the September term I suddenly realized how idiotic it was so I left off looking at him. He was rather hurt at first I think, but he soon recovered and he makes eyes at Barbara Tox and Gwen Smith now.

But in the summer holidays last year I met Ronald. We were all on the Broads for a fortnight. It was at Oulton, and we were moored alongside a funny little houseboat where an old bachelor spent most of his time. Ronald was his sort of manservant. He was quite a common sort of youth, but rather good-looking. I’m sorry to say I went quite dippy over him and gave Daddy some chocolate to give to him. I wonder if he liked me? He noticed me I know – he used to watch me! Another romance where I never said a word. Perhaps it’s just as well – he was only a fisher lad – but my heart just ached and ached when he went away. I wish I had a brother about Ronald’s age. Leslie’s a dear but he’s 24 now, and what is the use of a brother the other end of the world? All that day I felt pretty miserable and when we moored just outside Reedham I went for a long, long walk all by myself along the riverbank, and thought things out and finally conquered. I came back because it began to rain. I’d been out an awful long time and they were getting anxious and had come to find me. They were awfully cross and rather annoyed they hadn’t found me drowned in a dyke or something – no Jean, that was horrid of you. I think I cried in bed that night and I know I prayed for Ronald.

I determined not to have any more weak flirtations like that. I’m awfully weak and silly, I’ve been told that numbers of times. That was the 6th. I wonder who’ll be the 7th? No, I won’t even write what I think this time – but he goes to Cambridge and Margaret says he’s growing a moustache – and oh Jean be quiet, you did fight that down once, don’t bring it up again. Oh, I do hope nobody reads this – I should die if they did.

What shall I write about now? I know – my past cracks. It was when I was a queer little day-girl in Upper III when I first noticed Lavender Norris. Oh she was sweet! I went absolutely mad about her. She was awfully pretty with long wavy dark hair with little gold bits in it, and dark eyes. Peggy Saunders was gone on her too. I found a hanky of hers once underneath my desk. I gave it back to her and was coldly thanked – she was talking to Miss Prain at the time. One Xmas I sent Lavender some scent of her own name and she wrote back such a sweet letter. We were getting on famously when the next term she got ’flu and a whole crowd of us wrote to her and someone said I was pining away for her. I did write to her again in the Spring hols but she never answered.

She left in the Summer term 1923. Peggy used to write to her and once she told her about Mummy’s death and Lavender wrote back and said how sorry she was and sent me her love. Angel! I see her sometimes when she comes back as an Old Girl but that is all. If she was to come back again I should still be mad about her I’m sure – but at present Miss Wilmott [AW] claims my affections. Everybody knows I’m gone on her and grins knowingly at me and I hate it. I’ve walked with her too – I and Veronica – but on one awful walk I shall never forget Veronica did all the talking and I couldn’t think of a single thing to say. I came home feeling so utterly depressed that I could have howled. I remember some agonizing meal times too that term, sitting next to AW. They are too agonizing ever to write here.

She smiled at me once, quite of her own accord. It was the 2nd of June and we had to go for walks. We were waiting by the gate when I looked up quickly and she was looking at me rather funnily and then she just smiled! I nearly died. She’s never done it since – except once, again that term, when I held the door open for her. I went into ecstasies in the dorm. That term was glorious all through.

Sunday, 19 April 1925

Yesterday afternoon Daddy and I went and fetched the car from Harris’s. It had been there to get mended. Daddy and I were going to Marlow and Daddy backed into the tree and bent the front axle and crumpled the mudguard to nothing. Harris came down to fetch it on Tuesday and promised it us on Saturday, but when we got there the mudguard hadn’t come back from the makers, so we took it without. It does look funny but the car goes alright. I do love going out in it so – being able to go and see one’s relations and friends.

Thursday, 23 April 1925

We’re down at Torquay at last! Glorious place! We started on Tuesday morning about 9 am and after fetching Miss Watson we carried on till Andover, where we stayed for lunch. Andover is in Hampshire. Daddy drives awfully well! After we left Andover we went on to Yeovil in Somerset. We meant to stay the night there but everywhere was full up so we went on to Crewkerne. The hills were something awful for the car, but oh the view from the tops was so lovely. Just after we left Newton Abbot something went wrong with the car.

Monday, 27 April

Home again. Such a lot has happened. I shall never forget this trip as long as I live – never.

Daddy has always addressed Miss Watson with more than usual politeness and kindness. I have wondered often if he meant anything. And when we started on this trip my heart grew very heavy. He seemed so, so, I don’t know how to call it – so very nice to EW, and I began to think thoughts, thoughts I could not get out of my mind, unbearable thoughts. Oh Mother dearest! My heart grew heavy for you, darling one – it seemed too grotesquely untrue that Daddy could be forgetting you so soon. Jesus alone knows my heartache when Daddy lingered over saying goodnight to her at Crewkerne in the semi-dusk, and tears would come when I got into bed. I was jealous too – I thought, oh Daddy might not love me so much now. And then it rankled a bit to think of her coming into our home and taking your place.

The next day we arrived at Torquay and we went to see M Beaucaire (the film) in the evening, and it was glorious and daddy was so nice and dear to me after and I was so much happier.

And then the next day little things cropped up all day – things he said to her, looks they exchanged. I grew sad again until Ethel – yes, I shall call her that – changed quite early for dinner. Just before 6.30 Daddy came in and sat down. In my heart of hearts I knew what was coming. (I had pictured a sort of scene to myself, something like this: Dad comes to me and says, ‘Jean darling, we shall have someone to look after us at last. Ethel has promised to marry me,’ or words to that effect. I knew tears would come and he might say, ‘Why Jean, aren’t you pleased?’ Perhaps then I’d say, bravely gulping down the tears and smiling, ‘Oh yes Daddy, I’m very pleased, but Daddy, have you forgotten mother so soon?’) But he just sat in the chair and watched me undress for a while and then he said, ‘And what do you think of Miss Watson?’ So I naturally said, ‘I think she’s very nice,’ but I had to bite my lip hard. ‘Jean,’ he said, ‘I want to ask you a question.’ I knew what was coming but I feigned an interested surprise. ‘How would you like someone to come to live with us?’ I just slipped into his arms and cried, and I tried to get out about Mother but it just wouldn’t come. But oh he was so nice. I never knew I loved him so much until that moment. He explained that he’d thought of it now for some weeks, and that Mother had told him before she died that he was free to marry again (dearheart, that is your sweet unselfishness all over again!). He thought Ethel the nicest girl he knew and it would be a companion for me. His friends had often said to him, ‘Pratt, why don’t you get married again? You’re killing yourself with hard work.’ And then he said, ‘But Jean darling, if you think there is anything in this plan that might come between us I will throw up the cards at once, for after all you are all that I have got now and nothing must come between you and me.’

I couldn’t have him sacrifice so much – such love must entail a sacrifice from me. My heart sank and sank, but I said bravely that I was quite quite sure it would be all right and he need not worry. And he kissed my hand and said, ‘Thank you.’ And he also said that he had not asked her yet, but he must risk that. But when he had gone – Oh Mother, to think of seeing anyone else in your place. I never knew I loved you or your memory so much. So I came down at 7 cool, calm and collected, faintly perfumed with lavender. That evening we went to see Norma Talmadge in ‘Smilin’ Through’.

We came back along the coast – much worse hills but such pretty country. And I felt tired and sad and a little exhausted, but the level, smooth stretch of sea peeping between the graceful lines of the cliffs seemed to comfort the innermost recesses of my soul. And when we lost sight of it behind high hedgerows I ached for one more sight of it.

I became drowsy and rather cross, and across Salisbury Plain it began to rain and I tried to sleep, until Daddy bumped into a cow. The cow’s mild expression of pained surprise tickled me, so that I sat up once more and recovered my spirits.

I have thought the matter over a good deal recently and I have come to the conclusion that it is a very good sensible thing. The only fear I have now is what our relations and friends might say. She is very nice and kind, she can listen to Daddy’s business affairs much better than I can and understand. She will be such a companion for Daddy while I’m at school. But Mother your memory will always linger: there are your clothes that I cannot wear, your jewellery, the little things you gave me, the letters you wrote, the books you read, the piano and your music. And most of all that large photo of you in the dining room with your sweet, sad eyes, always smiling at me wherever I am in the room.

I went to see M Beaucaire at the Crown Cinema. That was the 2nd time I’d seen it but I loved it more and more. I have ordered the book at Smith’s and I’m longing for it to come. After seeing good films like that I have a strange feeling that I want to film act and to act well. I’d love to just make people wonder, envy, admire, to be famous, to be too good for any petty criticism and have certain people I know say, ‘Fancy – Jean Pratt! And when I knew her one would never have thought her capable of it!’ I just want to act, to live, to feel like someone else, to live in a real world of Romance. I know it would mean hard, hard work and many disappointments and heartbreaks, but I should love to feel that I sway men’s hearts to a danger mark, and women’s too for that matter. Last night Daddy, Ethel and I went out to a big Conservative meeting dinner, and I’m sure I looked so nice. It is the sweetest frock – very pale blue georgette, cut quite full over a pale blue silk lining. Right down the middle is a piece of silver lace about two inches wide. I wore very pale grey silk stockings and silver shoes. I also wore a blue and mauve hairband and displayed a mauve crepe-de-chine hankie in my wristwatch strap. I saturated myself in lavender water. For the reception I wore while silk gloves – I shook hands with the Duke of Northumberland. I do not like him very much – he has ginger hair and a moustache, a prominent nose and weak chin and white eyelashes – ugh! The dinner was great and some of the speeches were quite nice.

Coming home from Oxford Circus I had to be most tactful. I pretended to be frightfully sleepy and closed my eyes half the time and didn’t listen much to their conversation. When we arrived at Wembley Daddy said, ‘I hope you don’t mind Jean, but we’ll see you indoors and then I’m going to take Miss Watson home.’ I yawned and said, ‘Oh I don’t mind a bit, all I can picture in front of me is bed.’ Oh Jean, Jean, Jean – may your sins be forgiven you. When they had left I flaunted about upstairs in my nice clothes and did up my hair and admired myself in the glass and did a little film acting on my own. Then I thought I’d better hurry into bed – I heard it strike one and Daddy hadn’t come back. Then I fell asleep. He’s been in an awfully good mood all day today so I suppose his midnight vigil was satisfactory. Somewhere deep down in my heart it hurts.

Thursday, 7 May I

t’s over a week now since I last wrote my journal, but there are several good reasons. First, I got M Beaucaire the novel, and, not liking it as much as the film version, decided to write my own account. Second, Miss Floyd the housekeeper has been away for a holiday, so yours truly has had to light the fires and peel the potatoes. Thirdly, IT’S HAPPENED!!!!! Yes, last Wednesday evening about 11.45 I was still reading and Daddy came in saying he’d gone to Ethel’s and ‘It’s all settled!’ And he looked so happy.

Ethel is so sweet and nice to me. Daddy was busy buying new shirts and suits etc. It’s going to be awfully nice, and everybody’s very pleased and excited.

Chapter 2. Jean Rotherham

Friday, 30 April 1926 (aged 16)

Just over a year ago now since I began my journal but I have not forgotten. I am twelve months older now and things are different. I must keep this journal all my life – I just must.

Ethel makes a topping little mother she really does, and to see the good she has done my Daddy makes me feel indebted to her for ever. So as to give the connecting link between now and then: My diphtheria two days before their wedding, the hospital on their Day, the weary long drawn weeks there, the first one of aching homesickness, the fighting off of despair. And I came nearer to God than I had ever done in my life. They tell me that I nearly died, but He chose to give me my life.

Then that glorious holiday in Cornwall, Xmas, we got Prince (airedale), mumps, home again for three weeks, Jean Rotherham. I wonder why I write this? It is not so much the big events I want to record – it’s my feelings, my exact thoughts at a certain time. Perhaps in some future generation, when I am dead, they may read these words I am now writing. I wonder who those ‘they’ will be? Perhaps they will think of this as ‘grandmothers writings’ or perhaps as ‘old Miss Pratt’s’. And why have I that feeling at the back of my mind that no-one will ever read this? But if anyone ever does read this – if you ever do – Reader please be kind to me! I am only 16 at present, and just realizing life and beginning to think for myself. It’s all very thrilling in its strange newness.

This time next week I shall be back in that strangely bittersweet prison Princess Helena College. There is not another school like it in the world. To think I’ve got to go back – that I have to go back to orders and discipline, to Miss White and Botany, to the weary monotony of daily routine, to that conspicuous game of cricket! On the other hand there’s Jean Rotherham, whom I shouldn’t really mention at all here or anywhere.

Then there’s Miss Wilmott, the fun and laughter and companions of my own age, the Military Tournament, the sports and Junior party, the long summer holidays and THEN the event of events – Leslie’s homecoming! To go back to Jean R. The less said the better because I am going back to fight my self-control. She is younger than I am but I think her very sweet, though no one else knows it. I have only told Margaret because I must tell someone.

I wish I wasn’t so fat! I’ve gone up 10lbs again this holiday. It’s too sickening for words. Next holiday I must keep myself more in hand. I am now 10stone and it simply mustn’t be – at school last term I was 9st 4lbs.

Monday, 2 August

[In red ink.]

I’m sorry there’s no other ink to write with but I must write. I could never sleep after reading what I’ve read.

Lavender is dead. Dead. It happened last Saturday evening so the paper said, at Brooklands. I shall keep that cutting and the last photo I shall ever have of her. Lavender – I must have really cared an awful lot because I’m feeling mighty sick. But I bet Mr Cyril Bone’s feeling worse, if he can feel at all. I can’t send you anything for your grave because I don’t know where to send it, but I shall never forget you. And somehow I’m glad you didn’t live to get old and ugly, but died still lovely: ‘Whom the gods love die young’. Yet it’s awful to think you had no time to say goodbye. No one will know how much I really cared.

Helen Lavender Norris was the passenger in the racing car being driven by Cyril Bone at Brooklands circuit near Weybridge in Surrey when it crashed at 100mph. She was 20.

Sunday, 8 August

Next school year I’ve got to work like blazes for the General Schools examination in June. Everyone is so discouraging at school. That old beast Miss Pilcher informed me quite cheerfully the last day at lunch that I had no earthly for Schools next year. But Miss P we shall see. Of course it’s absolutely idiotic of her to say that, as I feel inclined to say, ‘Well seeing as I’m not going to pass, and you seem so sure of it, why should I bother to work this year at all?’ I wish I’d thought of it at the time.

As to JR – she was six weeks in the sicker poor kid, with a poisoned foot, and life was extraordinarily dull while she was there. We were socially poles apart – not even in the same cloakroom. But I think she knows I rather like her, and anyway I’ve caught her looking at me more than once. She is seen at her best in a tennis match. She’s younger than I am, but when I see her playing and forgetful of everything else there is no sweeter sight on earth.

The day after I came back from school we went up the High Street and I got the simply rippingest things.

I. Fawn tailor-made coat – stunning affair that matches hat, stockings and several things I already possess.

II. Cotton voile frock. White with patterns of yellow roses round the navy neck and sleeves (am going to wear it this afternoon).

III. Stumpy umbrella, black and white, carved handle, birthday present from Ethel in advance. Topping one.

IV. Fawn gloves.

V. Cream pair silk stockings – unfortunately wore them for tennis yesterday and made irrevocable ladders.

Oh dear, I do love clothes and making myself look nice. It really makes life worth living, but Ethel laughs at me. I’m getting frightfully conceited, and I really wish I was slimmer. But sometimes I think my legs and ankles aren’t really such a bad shape in silk stockings, and I’m beginning to wonder if it’s purely imagination or are my eyes really quite a nice blue on occasions and sometimes quite big? I know I’ve got quite a nice mouth – I was told so once at school in ‘Truths’. They thought it was my best feature. I overheard Mrs White say that she thought I’d got lovely skin, but I really do not like my complexion. My nails are something appalling and my hips really are too big. In fact I am big – horribly large – and ‘well covered’ as Ethel puts it, or ‘stout’ as Mrs White said. It’s been a foregone conclusion from the days of my earliest childhood that I’ve got pretty hair, but I really am beginning to just loathe frizziness and it’s getting a really most uninteresting colour, and much thinner since I had dip. And then I wear glasses – that always puts people off a bit!

I was staying with Margaret, and she’s got hold of two awfully nice boys who half-promised they’d come to the cinema with us. When she told them I wore glasses they began to kick horribly. But she told them I smoked and liked funny stories (the kind you’re not supposed to hear), so they thought I’d be all right after all. But there was some difficulty about another girl and they couldn’t come after all. I loathe being thought a prig.

Wednesday, 1 September

Mullion again and the clear sea air!

On Monday we started at a quarter to nine from our house. Ethel and I were so tightly packed into the car, and so surrounded by ‘impedimenta’ we didn’t quite know where we began or ended. We met Uncle Charlie and Auntie Ruth on Ealing Common at 9am, and after that we couldn’t get the car started, but at last with Harold’s help we were off. On the Bath Road Daddy decided the oil gauge wasn’t behaving properly so he hailed an AA man and they spent half an hour fooling with that. We went to Andover for lunch, and Ethel, Daddy and Uncle all slept afterwards in the lounge upstairs – the three beauties – until the maid floated in loudly and woke them with a start.

Sunday, 5 September

Leslie is coming on Tuesday! Not next month or next week, but Tuesday. I’m getting just a little nervous. Will he have altered too much? Does he want to see me as much as I want to see him? How will he get on with Ethel?

Monday, 6 September

Tomorrow morning at 6.30 Daddy and I go to Helston. Leslie. I mustn’t forget to brush my hair well. What shall I wear tomorrow? Oh Leslie, just one wild beautiful fortnight and then school and hard work. I mustn’t make a sound tomorrow morning…

Thursday, 9 September

It’s 10.45pm and everyone but me is getting into bed. Writing by candlelight. Tonight let us deal with the biggest subject I have in my life at the moment: my brother. A tall brown man who is at once so very familiar and yet such an utter stranger. I think he feels just as shy at having to deal with a growing-up younger sister as I am at having this manly yet very brotherly brother. He is not used to England yet after three years in the wilds of Brazil. He has the most extraordinary eyes, grey-green, a little piercing, honest eyes.

All the same, it doesn’t seem so wonderful – the anticipation was far sweeter than the realization. It usually is, but it wasn’t his or anybody else’s fault. I had anticipated too much. After all the excitement was over on Tuesday I was worn out and dead tired and disappointed. I somehow felt he found I wasn’t quite what he expected. I cried after I’d blown the candle out. Sometimes you have to. I would never cry in front of anyone if I could help it. But in the dark, just sometimes.

Saturday, 11 September

Yesterday morning a film company came down to the Cove with all their paraphernalia. Most thrilling. They were having a sort of picnic when we left for our lunch, and Geoff and I bolted our food to come down again to the Cove as early as we could. They had collected on the rocks just below the Mullion Hotel, and we clambered up the cliffs and got a topping perch. There were at least a dozen of them.

The heroine, one of those pretty fluffy little creatures with a child’s figure, a springy walk and an American accent – she was wearing an orange cap with a long silk tassle over one shoulder, a blue Eton sweater and a green shirt with white shoes and stockings. And her hair was very, very fair and fluffy – suspiciously fair.

The hero – I should think he was an Italian – anyway, something foreign – very tall and slim, black hair just going grey, quite good-looking with clean-cut features and very even teeth. He was dressed as a sailor in long dark blue trousers and a queerly worked belt in gold and black. We discovered today that he is Carlyle Blackwell and the girl Flora le Breton.

Well they didn’t do much yesterday afternoon. It was a dull, heavy day and they couldn’t get on without the sun. They made up their faces, and fooled around quite a lot, but nothing happened so just about tea-time they packed up and went. We left a lot of them eating mussels at the Gull Rock Hut.

This morning directly after breakfast Geoff and I flew down to the Cove to see what was happening. They had started – at least the hero and heroine were practicing a most touching love scene and a sad farewell. So we got some sob stuff gratis. But just as they were getting the cameras ready the sun went in and presently it began to rain, so they all packed up again!

Directly after lunch the sun came out. They went through the caves onto the beach and started rigging up palm trees. They didn’t do much on the beach – only just rigged up the palm trees and took them down again. The producer and his wife bathed, and presently they started packing up.

The film was The Rolling Road. Released in 1928, it was co-produced by Michael Balcon some years before his Hitchcock and Ealing classics.

Saturday, 8 January 1927

Last night I didn’t get to bed till past midnight. Leslie and I sat up talking, and he mentioned the fact that perhaps after his next leave (I shall be 21 then) it is possible I might go back with him and ‘keep house’, provided of course he didn’t get married in the meantime. He said, ‘I don’t think I shall ever get married – of course you never know your luck.’

The idea thrills me to the core: to get away from here, from Wembley, just for a little while, to see different places and people. I know that I shall be in love a hundred times before I find the right man. I don’t want to get married – not at least to the struggling domesticated life which seems to belong to every man I know. I want someone just overpowering, who can dance divinely with me, who likes much the same things as I do, who isn’t too punctilious or particular, yet dresses well and looks well and is well, who doesn’t mind spending money. I don’t think I want him to be too rich, but just well enough off so that we can live comfortably, enjoy life and help others, those who really need it. He’ll have to be taller than me of course, quite good-looking, not too much so though, he must be extremely witty and popular, a hard worker without showing it, reasonable and sympathetic, dark, and he must be endowed with much the same gifts and ideas as Leslie. He must be English too. In fact he’ll be a man very difficult to find, and when I do find him I’ll think myself unworthy.

I am so lonely, yet who am I to complain? You are tired Jean. But stand up to these pinpricks, grit your teeth, grin and go on, so that when the blows come with God’s help you won’t go under. Poor little lonely soul. If I could give you back your mother I would. But hold up your head and never let the world know. It doesn’t want to know. You are of no consequence to it, so why should it bother?

Monday, 17 January

On Thursday I go back to the work and the weariness and the routine, the fun and the laughter and the dread of failure. Exams! That will prove if my last term’s victory was worthwhile, was sincere. It will seem just impossible to think that someday there will be no returning, that I shall have to say farewell to the place which has played the biggest part in my life so far. And after that? The office with Daddy to see what architecture tastes like, and then perhaps more work and exams and a career…when my soul cries out for dancing and film work. I think that after a while you would grow very tired of dancing, and as to films it means very hard work and a lot of pushing.

Yet again if I did take up architecture for a career – and I should never dare to do so unless I was sure I could make a success of it, for Daddy’s sake – there’ll come a time when I’ll have to toss up between that and a home and babies. It’ll be mighty difficult, but time and these pages will see.

The smell of eucalyptus, the fluttering of the fire, the ticking of the clock, the occasional rustle of the paper as Ethel turns to read it, her spasmodic conversation, sometimes the dog asleep beneath the table – home and nothing to do. Life would be awful like that.

Monday, 7 February

I have come to the conclusion that I am rapidly ‘growing out’ of school. This routine, these petty little rules, this kind captivity. But as HP pointed out yesterday it is like climbing a hill. You are dying to get to the top but there’s still a long way to go. The only thing is to climb – so one climbs.

Tuesday, 8 February

I’ve had a simply priceless day. It began with gym. I had a hole. Nobody could give me any wool to darn it with and I had no black ink. The only thing to do was to wrinkle my stocking, take deep breaths and trust to luck. Which I did. AW passed calmly by. She never saw it, all the lesson. But I simply couldn’t jump. Then we went to see the Flemish art exhibition at Burlington House. We went by charabanc. The most interesting part was when we sat down and just watched people. I only saw one really well-dressed woman there. English women do dress badly. I do hope that when I leave I’ll be able to turn myself out better than most.

Sunday, 27 March

Sometimes I hate everyone, everything. Last night I loathed the thought of the life I’ve got to live: inconspicuous, complacent. I want to do great things, to be great. I can’t bear to think of that office, to pass my years insignificantly as an unsuccessful architect. Why won’t Daddy see these things? I want to do everything people think me incapable of.

Saturday, 9 April

I am home again. This term’s report is a simply amazing one. Miss Harris said to me when I was going, ‘Hope you have very jolly holidays Jean – you deserve them.’ My English has developed amazingly – that essay on ‘Night was rather a hit. I wonder if I could get Matric? It would be such a splendid triumph.

Last night at half past ten Leslie took me for an hour’s run in Pipsqueak. Somewhere out Edgware way. As we sped along some straight wide road Leslie murmured, ‘The road is a river of moonlight/ Over the dusky moor.’

It was rather like that – all the flat uninteresting country on either side hidden by a misty darkness, only the moon and the white stars in a clear hard sky.

The thrill of the hour, of speeding through places made totally unfamiliar by the night, passing alone with my brother at midnight. Such things are stored in gold in my memory.

Tuesday, 24 May

I said goodbye to Leslie over a week ago. We all got up very early, and Daddy and I went to see him off at Euston. I put on my holiday clothes to see him off. I wonder if he saw the tears in my eyes when I kissed him goodbye. He was standing at the back of the carriage in the shadow – silent – and the train slowly, heartlessly, took him away. All those golden weeks were over. Three whole years, and the most terrible time in front of me.

Saturday, 28 May

We played Luckley this afternoon – cricket 2nd XI. Theirs was more or less an A team. Anyway they won 80-74. I made 9 runs, caught one person out, and took one wicket.

Saturday, 11 June

Today I went home. There were cherries, strawberries, tall blue lupins, white foxgloves, geraniums, early roses. There was the newly painted kitchen, but Leslie’s room was empty and silent and a white dust sheet covered the bed. Things he had left behind – magazines, ashtrays, the fencing foils, an old coat – were scattered about my room waiting to be cleared away.

Then I came back to school again, and the Junior party was simply wonderful. They acted Peter Rabbit and Benjamin Bunny, then we made handkerchief animals, each form competing. Then we had light refreshments! There were scenes from ‘Wind in the Willows’, then hide and seek. There is only one more week before the exams. French oral is on Weds.

Sunday, 12 June

I am in a most amusing and entertaining position at the moment. I think I may safely say that I have no attachments to particular people to consider. I stand a little apart, alone yet never really lonely. There are always plenty of people who are quite pleased to have me if I want to come: Laura, Phyllis Yeld, Rosemary G, Doreen Grove, Phyllis Stephenson and Betty Andrews. The latter I like most of all, yet I don’t feel pledged to her in any way.

Then there is Gwyneth and Dorothy. There is only one way to deal with Gwyneth. That is to elude her for a time. I am not strong enough to dominate her or to keep her as my friend. You have to make her run after you. It is a deadly mistake to run after Gwyneth. Gwyneth is an incorrigible gossip – you never know what she might be saying about you behind your back. Today we were in the garden and we could see Laura P and Phyllis taking each other’s photos, and Gwyneth made some unwholesome remarks about them. They couldn’t possibly have heard from where they were, but after supper I was sitting with Yeld, Prideaux and Grissell, and during a discussion about people generally Gwyneth and Dorothy were mentioned. ‘I always feel,’ said Yeld to me, ‘that those two are watching us. When Laura and I were taking photos of each other in the garden I was sure they were talking of us.’ I chuckled inwardly.

Thursday, 23 June

The worst of them are over – finished. Arithmetic, History, Geometry, French, Algebra and English. I have washed them away in my bath tonight and now I am between clean sheets and in clean pyjamas.

I do not think I have got Matric. I wrote a fairly decent essay on Modern Communication. The Grammar I think I did fairly well on too, perhaps I have got Credit. The Set Books I am not so sure about. Algebra – of course that was unspeakable. I have obviously failed in that. The French was better than I expected. The Geom was better in comparison to the Algebra. History of course – well, I cannot say. Miss Stapley said I was her ‘hope’ just before I went in. One question we have all done wrong: the Civil War of 1649 we all took to be the First Civil War, 1642-46. The Arithmetic was amazingly easy – too easy I think. I have yet to pass in Drawing and Botany, which I think I shall do.

Although it has been a very long week, this week has been by far the nicest. The free half-hour in the garden before the exams, swinging high up level with the gym windows and the wind in your hair, the scent and colour of the herbaceous border, the thrill of being a candidate – the privileges and prestige! It is all over now and the days will never be the same.

Tuesday, 28 June

I had thought there was no heart left in me and I had killed that wayward passion for Miss Wilmott long ago. But tonight as I came in late from the garden at 8.45 she came in through the doors into the Back Hall. There was no-one there but she and I and I was in a hurry, but as I dashed around the corner of the stairs I said ‘goodnight’ as she passed. The light was dim and the shadows long, but she turned her head and I think she may have smiled as she said ‘Goodnight Jean’ in the way she used to do two years ago. I knew in that moment I could have died for her and that I shall never be able to forget. ‘Those who dream by day are cognizant of many things which escape those who dream only by night.’ I believe that she may grow to care more than I have ever cared to hope. What can I do? She lives in a world of games and speed and swift thought, – hard practical ideas – and straight, slim eager girls who love to do difficult and complicated things on ropes and bars and things and who scorn such lazy ones as I. She said, ‘So long as you try I will help you – I will help you for ever if only you’ll try.’

Monday, 25 July

It has come, that dreamed-of long-dreaded hour when I sit alone for the last time in my room at PHC. Miss Parker has made me an Old Girl. I shall be able to come back next term and see those who are not leaving. I cannot believe that it is all over. I have not been able to see or speak to AW. But at least I can write.

Wednesday, 27 July

And now I am home again. It is half-past six in the morning and I am going to get up soon and make the tea. It is raining.